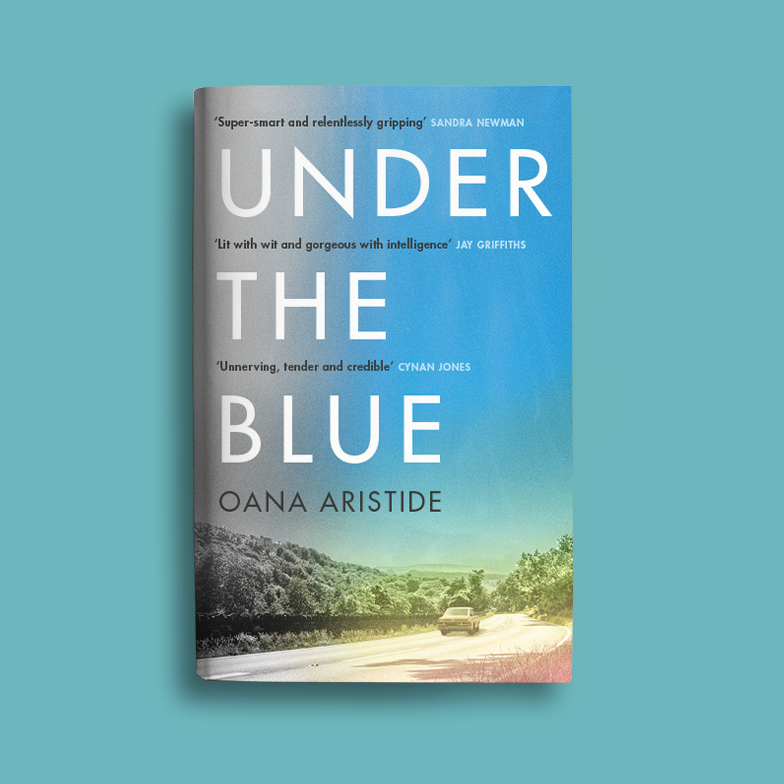

‘A super-smart and relentlessly gripping addition to the eco-fiction genre, Under the Blue is by turns chilling, incisive, and casually hilarious. It also features one of the most convincing sentient-AI characters in recent fiction’ Sandra Newman, author of The Heavens

‘A super-smart and relentlessly gripping addition to the eco-fiction genre, Under the Blue is by turns chilling, incisive, and casually hilarious. It also features one of the most convincing sentient-AI characters in recent fiction’ Sandra Newman, author of The Heavens

A road trip beneath clear blue skies and a blazing sun: a reclusive artist is forced to abandon his home after a mysterious plague sweeps the nation. He is followed by his neighbour and her sister, who have a plan: to leave the country and travel across Europe to Africa, where it’s said to be safe.

Meanwhile two computer scientists have been educating their baby in a remote location. Their baby is called Talos, and he is an advanced AI program. Every week they feed him data, starting from the beginning of written history, era by era, and ask him to predict what will happen next to the human race. At the same time they’re involved in a increasingly fraught philosophical debate about Talos’ existence: is building an AI for the purpose of predicting threats to human life an ethical – or even worthwhile – pursuit?

These two strands come together in a way that is always suspenseful, surprising and intellectually provocative: this is an extraordinarily prescient and vital work of fiction – an apocalyptic road novel to frighten and thrill.

Read an extract from the opening chapter below.

Pre-order your copy

It has never taken him this long to finish a project. The problem, he knows, is that he wants too much from this one painting. She’s like a woman, the canvas: you cannot approach her in despair. She has to know that you are free to walk away. You do not come to her begging, reeking of guilt.

He has stepped back from the canvas, meaning to take it in from a distance, when he sees on the road outside his studio a man and a woman, both wearing gas masks, both loaded with suitcases and backpacks. They throw their luggage into the boot of a car and take off with a screech.

Gas masks?

He brings a hand to his forehead, makes an effort to step out of himself, to focus on the matter at hand. To make sense of what he sees.

How long has it been since he last spoke to someone?

‘In light of recent events …’ last week’s text had started, the one from the course administrator that informed him his classes were cancelled. He assumed … What did he assume?

He sits in front of the canvas, frozen, for a long time. No action seems adequate or desirable. He finally stirs when he hears noises on the landing. He goes to the door and looks through the peephole. Nothing at first, then Twenty-Two comes rushing along, fumbling with her keys, dropping them. She is sobbing, and when she unlocks her door she almost falls into her flat.

He steps back from the peephole, looks down at his bare feet. He has taken off his shoes and socks because of the heat. His toes are rosy-pale and dainty, clinging uncertainly to the cool tiles. The whole of him, that’s what he feels like all of a sudden. Unshod, exposed, unprepared.

He takes a few steps towards the living room, intending to turn on the TV, but then, remembering the power cut, he reaches for the light switch, jiggles it up and down. The light bulbs stay dark. Weakly, he wanders around the flat looking for his mobile. He last checked it a couple of days ago. His phone is old and dumb, but its battery lasts ages.

He finds it on a shelf in the hallway. It still shows one bar.

He slides down along the wall and sits on the floor. Who to call? He tries his friend David, gets an unavailable message, then Matt at the gallery, whose phone rings and rings. He tries two more numbers and finally, desperately, the course administrator at the Academy, the last person to contact him. He hears a scratching noise and thinks what’s-her-name has picked up. ‘Hello!’ he shouts. When there’s no reply, he looks at the screen. The phone has died.

He remembers the deserted reception desk downstairs, the empty streets, the homeless person asking him where everyone’s gone. The neighbours with the gas masks.

People have left. Whatever happened, it has chased people out of their homes.

That thought triggers something in him, and he finally acts with some urgency. The first thing he does is go to the studio and throw brushes, paints, solvent, canvas roll, a sketchbook into a plastic bag. He touches the canvas, knowing what he’ll find. There’s the skin, but underneath that the paint is wet. No way can he roll it.

He wonders how late he is.

He empties the fridge and the cupboards of food, puts pasta, sliced ham, tomato soup, frozen chicken thighs, tinned mackerel and baked beans in Tim’s old gym bag. There is already some food at the cottage; when he last left the cupboards were full of cans. He stands looking at the kitchen tap, considers taking drinking water. He remembers that the cottage is five minutes away from a stream, and moves on to the bedroom.

He starts packing clothes, but by now he’s lost the capacity to concentrate and just stuffs anything he comes across into a suitcase. He should have sat down and made a list.

Before he sets off, he pauses outside Twenty-Two’s flat and knocks on the door.

‘Hello,’ he says. He rings the doorbell. He thinks he can hear footsteps, feels she’s just beyond the door.

‘Do you need help?’ He tries to say this loud enough so she can hear, but without shouting.

Back in his flat, he tears out a page from a notebook and writes down the Devon address. ‘Harry (flat 23)’, he signs. He pushes it under her door.

He makes three trips to the underground car park, the last one with a bag full of wine bottles. The parking lot is even emptier than usual. He breathes heavily; remembering the couple with the gas masks, he has tied a scarf around his mouth and nose. He resists the childish, stupid impulse to sniff the air. On his windscreen, there’s an A4 flier showing a dotted map of Europe; it says ‘CONTAMINATION MAP’ at the top. He throws it in the car, he will make sense of it later.

As he drives off, the things he forgot to pack come to him in a neat list: razors, soap, loo roll, phone charger, lighter, any kind of medication. Drinking water for the trip.

‘A super-smart and relentlessly gripping addition to the eco-fiction genre, Under the Blue is by turns chilling, incisive, and casually hilarious. It also features one of the most convincing sentient-AI characters in recent fiction’ Sandra Newman, author of The Heavens

‘A super-smart and relentlessly gripping addition to the eco-fiction genre, Under the Blue is by turns chilling, incisive, and casually hilarious. It also features one of the most convincing sentient-AI characters in recent fiction’ Sandra Newman, author of The Heavens

In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado

In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado

Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women and Queer Radicals by Saidiya Hartman

Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women and Queer Radicals by Saidiya Hartman

To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life by Hervé Guibert

To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life by Hervé Guibert

A literary thriller about a pandemic, the rise of AI, and how – or why – we might save the human race.

A literary thriller about a pandemic, the rise of AI, and how – or why – we might save the human race.