We may be slipping into one of Jarett Kobek’s alternate universes, but we’re going to jump the gun here and say summer has *finally* arrived! While you’ve been buried under a wardrobe of linen reaching blindly for that stray picnic blanket, we’ve pulled together our summer picks to make your sun-soaking quest that much quicker.

‘Brilliantly funny … the best satire of our contemporary nightmare that you will ever see, and very possibly the last.’ Alan Moore

It’s 2019 and Jarett Kobek has done the only thing a dissident American novelist can do in those circumstances: he’s joined the party and written fantasy novel about an immortal fairy queen and a shadowy billionaire philanthropist sheikh called Dennis. Hilarious, provocative and unmissable, Only Americans Burn in Hell is the only novel for our certifiably insane times.

Read here: the office lobby of a global conglomerate – Google, Amazon etc

Pair with: coffee, painkillers, sweets

Watch after: The Good Place, Black Mirror, Who is America?

Buy your copy with 10% off & free UK shipping

‘Takes the issues raised by #MeToo and shows them as inextricable from more universal questions.’ Guardian

Trust Exercise is an enthralling, captivating novel about the treacherous terrain of adolescence, how we define consent, and what we lose, gain and never get over as we navigate our way into adulthood’s mysterious structures of sex and power.

Read here: a theatre cafe

Pair with: Kit Kats, Ice Cream

Watch after: Sex Education, Alias Grace, Thirteen Reasons Why

Buy your copy with 10% off & free UK shipping

‘It is not for the faint-hearted, but they should read it anyway.’ Peter Stanford

In The Beekeeper of Sinjar, the acclaimed poet and journalist Dunya Mikhail tells the harrowing stories of women from across Iraq who have managed to escape the clutches of ISIS.

Dunya Mikhail weaves together the women’s tales of endurance and near-impossible escape with the story of her own exile and her dreams for the future of Iraq.

Read here: bookclub

Pair with: honey, milk, canned soup, bread

Watch after: Black Crows, I was a Yazidi Slave, Where We Belong

Buy your copy with 10% off & free UK shipping

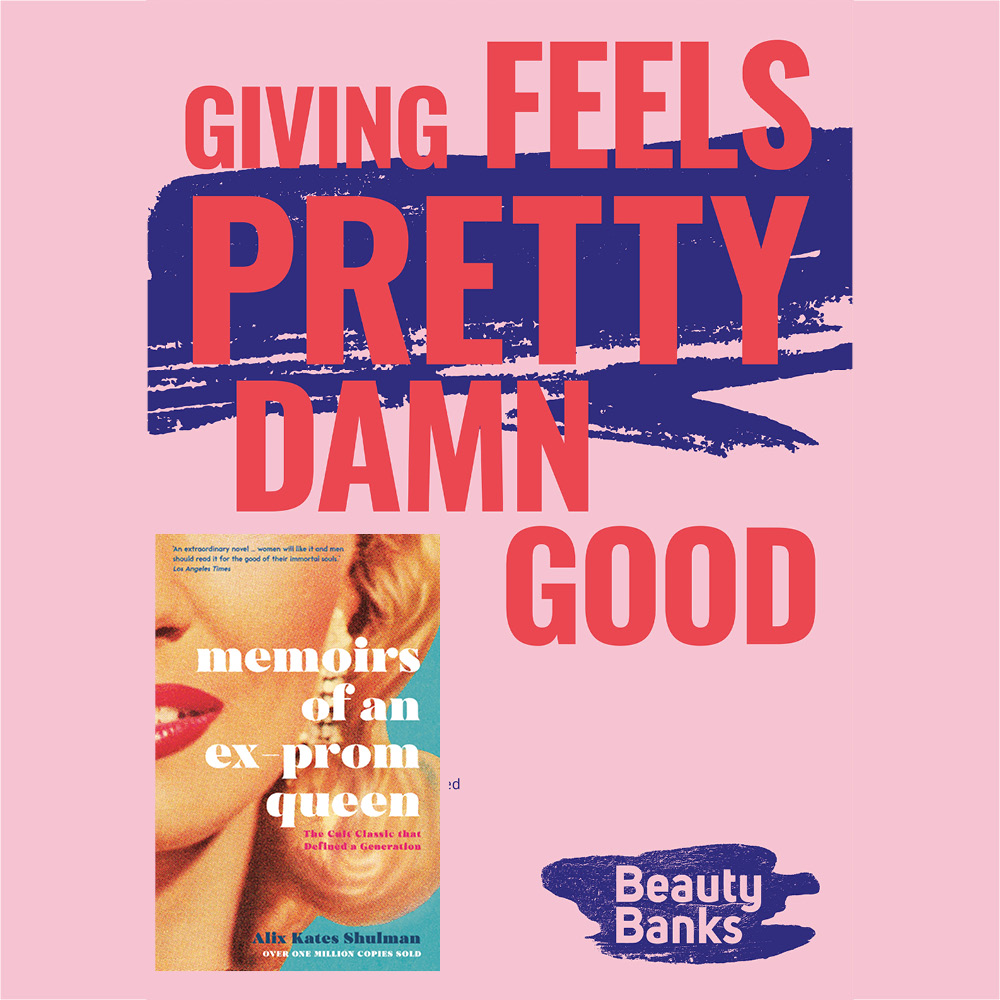

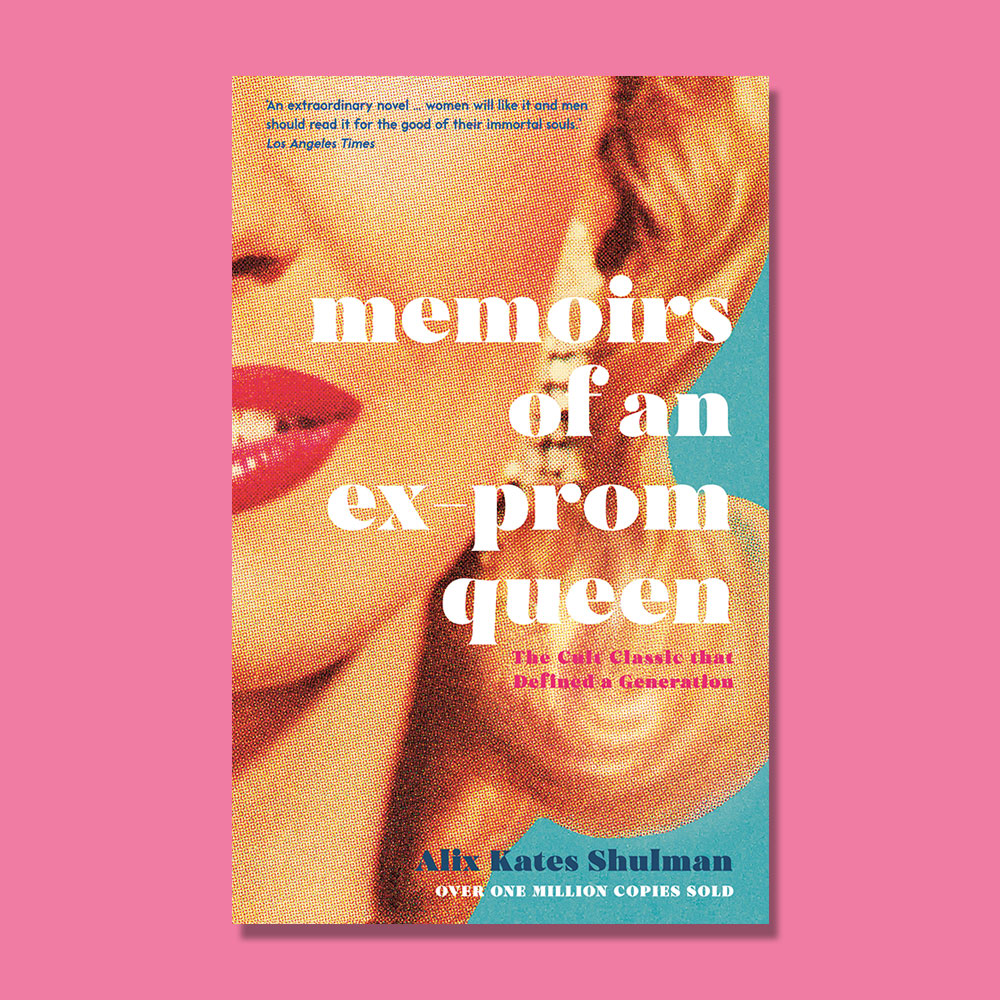

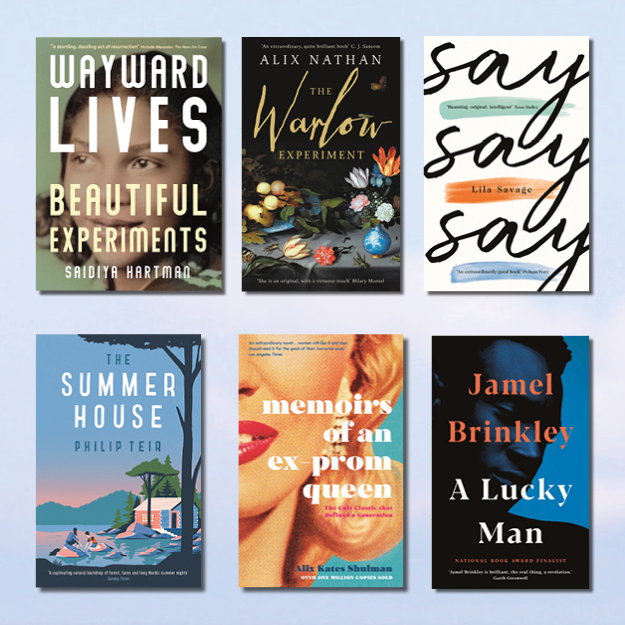

‘Memoirs Of An Ex-Prom Queen will make you laugh and want to smash the patriarchy.’ Red

Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen is a cult classic that defined a generation. First published in 1972, Alix Kates Shulman’s landmark novel follows Sasha’s coming of age through the sexual double standards, job discrimination and harassment of the 1950s and 60s. Five decades later, it remains a funny and heartbreaking story of a young woman in a man’s world.

Read here: The bath, wearing a tiara

Pair with: eggs bene, shrimp cocktail, éclair, baba au rum

Watch after: Dumplin’, Mad Men, The Good Wife

Buy your copy with 10% off & free UK shipping

‘Scandinavia’s answer to Jonathan Franzen.’ Telegraph

How do we live if we know that the world is about to end? From the outside, Erik, Julia and their children form a happy young family looking forward to a long holiday together on the west coast of Finland. But look under the surface, and their happiness shows signs of not lasting the summer. In the The Summer House Philip Teir transports us into a compelling summer drama about life choices and lies, about childhood and adulthood.

Read here: an Airbnb, around a campfire

Pair with: barbecue, new potatoes, Brita cake, wine

Watch after: Bonus Family, This is Us

Buy your copy with 10% off & free UK shipping

‘This is an extraordinary, quite brilliant book.’ C J Sansom

Herbert Powyss longs to make his mark in the field of science and sets up a radical experiment in isolation: for seven years a subject will inhabit the cellar of a manor house in solitude. The Warlow Experiment is ‘powerful’, ‘unsettling’, ‘extraordinary’, ‘brilliant’, ‘gripping’ and ‘unusual’ – well-deserved descriptors for an unforgettable novel. This eighteenth-century underground experiment gone wrong will leave you feeling extremely grateful for fresh air and sunlight.

Read here: a well-lit, cosy chair above ground

Pair with: porter, potatoes, green veg, orange jelly

Watch after: The Handmaid’s Tale, You, The Rain

Pre-order your copy with 10% off & free UK shipping

‘Insightful and endearing, this is a lovely look at friendship and human fragility.’ Psychologies

What’s the point of friends if you can’t share your secrets? The Gunners follows a gang of latchkey kids as they navigate the difficult journey through childhood to adolescence. One day, Sally stops speaking to the group and when they meet again years later at Sally’s funeral, everything has changed. Rebecca Kauffman’s generous tale of friendship in adulthood encourages us all to reflect on what separates true friends from the rest.

Read here: a swing seat, surrounded by childhood friends

Pair with: cereal, cookies, coffee, ramen noodles, Côtes du Rhône

Watch after: The Breakfast Club, Big Little Lies, Stranger Things

Pre-order your copy with 10% off & free UK shipping

FINALIST FOR THE NATIONAL BOOK AWARD FOR FICTION

No summer reading list is complete without a short story collection. In the nine unforgettable stories of A Lucky Man, Jamel Brinkley explores the unseen tenderness of black men and boys: the struggle to love and be loved, the invisible ties of family and friendship, and the inescapable forces of race, class and masculinity. A Lucky Man is a striking snapshot of the inner lives of men and boys caught between hope and expectation, duty and desire.

Read here: downing street

Pair with: burgers, hot dogs, potato salad, corn, beer

Watch after: When They See Us, Moonlight, Luke Cage

Buy your copy with 10% off & free UK shipping

‘Something quite special, unlike anything else I’ve ever read.’ Tessa Hadley

Ella is nearing thirty and she’s found herself in an unintended career as a care worker. One spring, Bryn hires her to help him care for his wife Jill. It’s not long until Ella’s entangled in their relationship and is forced to reconsider her understanding of relationships of all kinds. Lose yourself under a shady tree in Lila Savage’s debut tale of love and compassion and the fluidity of desire.

Read here: a landscaped garden, under a shady tree

Pair with: chilled sweet rhubarb soup, pad thai, Cup O’Noodles

Watch after: What/If, Gentleman Jack, Away From Her

Pre-order your copy with 10% off & free UK shipping

‘Exhilarating … A rich resurrection of a forgotten history.’ The New York Times

At the dawn of the twentieth century, black women in the US were carving out new ways of living. Wrestling with the question of freedom, they invented forms of love and solidarity outside convention and law. These were the pioneers of free love, common-law and transient marriages, queer identities, and single motherhood. Saidiya Hartman’s genre-defining history recovers the radical aspirations and insurgent desires of young black women in their invention of freedom.

Read here: your favourite cafe

Pair with: pitcher of beer, chop suey

Watch after: She’s Gotta Have It, Homecoming, Hidden Figures

Pre-order your copy with 10% off & free UK shipping

‘Absolutely absorbing, fascinating and indispensable.’ Alice Walker

A writer of the Harlem Renaissance, Nella Larsen’s novels are moving, characterful, and important. She pioneered writing about the conflicts of sexuality, race and the secret suffering of women in the early twentieth century. Critically acclaimed, both Quicksand and Passing speak powerfully of the contradictions and restrictions experienced by black women at that time.

Read here: the park

Pair with: White Rock, ginger ale, sandwiches

Watch after: Chewing Gum, Dear White People, Maya Angelou: And Still I Rise

Buy your copy with 10% off & free UK shipping