This article first appeared in our newsletter. To get gems like this straight to your inbox, sign up below.

Yes! Please sign me up to the Serpent’s Tail newsletter.

{{block type=”newsletter/subscribe” template=”newsletter/signup.phtml”}}

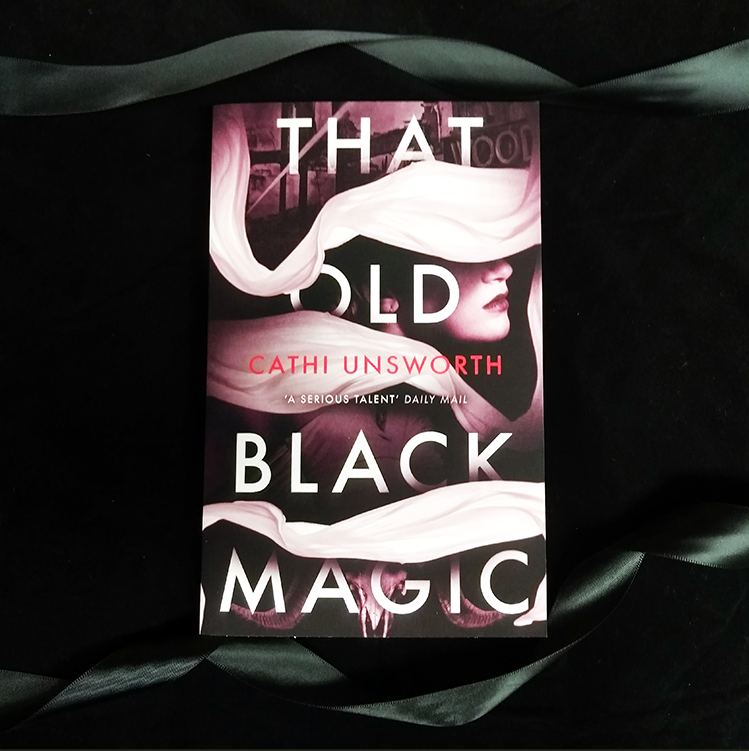

That Old Black Magic is the latest crime novel from Cathi Unsworth. This time, Cathi delves into the real-life story of Bella in the Wych Elm, a 1943 murder mystery – and tells us how she created a web of intrigue involving mediums, Ghost Hunters, music hall managers, Suffragettes-turned-Fascists and the corporeal spooks of British Intelligence …

When it comes to writing noir fiction, I have found that the most bizarre characters and plotlines are ones you just couldn’t invent. Which is why my books are based on real cases that have either remained unresolved or contentious to this day. In That Old Black Magic I combine one of each, intertwining stories of witchcraft from the darkest days of World War II, with a cast drawn from reality that even the most imaginative of scribes would be hard-pressed to invent. Mediums, Ghost Hunters, music hall managers, Suffragettes-turned-Fascists and the corporeal spooks of British Intelligence haunt these pages. Please allow me to introduce you to some of them.

When it comes to writing noir fiction, I have found that the most bizarre characters and plotlines are ones you just couldn’t invent. Which is why my books are based on real cases that have either remained unresolved or contentious to this day. In That Old Black Magic I combine one of each, intertwining stories of witchcraft from the darkest days of World War II, with a cast drawn from reality that even the most imaginative of scribes would be hard-pressed to invent. Mediums, Ghost Hunters, music hall managers, Suffragettes-turned-Fascists and the corporeal spooks of British Intelligence haunt these pages. Please allow me to introduce you to some of them.

I first wrote about Helen Duncan, the Highland-born medium who was the last woman to be prosecuted under the 1735 Witchcraft Act in March 1944, in my last novel Without The Moon. My interest was piqued about this still-controversial case by Tony Robinson’s BBC documentary The Blitz Witch. In the course of research, I discovered two more fascinating characters. Her ally, Hannen Swaffer, was Britain’s most popular and trusted journalist – despite being a self-professed Spiritualist and Socialist, neither of which would gain you much Fleet Street traction now. Her nemesis, Harry Price, was the founder of the National Laboratory for Psychical Research, who investigated the phenomena of mediumship as Spiritualism reached its peak of popularity between the Wars, was a member of the Magic Circle and President of The Ghost Club. While Swaffer, along with scores of distinguished witnesses, testified to Helen’s veracity at The Old Bailey, Price provided the prosecution with photographs of the medium projecting ectoplasm that looked suspiciously similar to cheesecloth.

Price, alongside the remarkable MI5 spymaster Maxwell Knight, weave together my two central stories. Knight ran a circle of agents throughout WWII who infiltrated the many strange, mystic cults with allegiances to the Nazis. His most infamous recruit was the traitor propagandist William Joyce, aka Lord Haw Haw, and his most famous friend the novelist Dennis Wheatley, who also worked in wartime counter-intelligence. In my fiction, Knight assumes the enigmatic form of The Chief. The case that binds them harks back to the April of 1943, when four young boys illicitly foraging in the grounds of Hagley Hall in Worcestershire made a grisly discovery inside a tree. Itself resembling a thing of nightmare, ‘the Wych Elm’, as it was locally known, was acting as coffin for the body of a woman, apparently ritually murdered and hidden there two years previously. Though no one came forward to identify her, graffiti started appearing across the region, asking: WHO PUT BELLA IN THE WYCH ELM? Is she the woman that my fictional detective, Ross Spooner, has been seeking since, on hearing the confession of a German spy captured in the Fens, The Chief sent him to the Midlands to find the elusive Agent Belladonna?

Price, alongside the remarkable MI5 spymaster Maxwell Knight, weave together my two central stories. Knight ran a circle of agents throughout WWII who infiltrated the many strange, mystic cults with allegiances to the Nazis. His most infamous recruit was the traitor propagandist William Joyce, aka Lord Haw Haw, and his most famous friend the novelist Dennis Wheatley, who also worked in wartime counter-intelligence. In my fiction, Knight assumes the enigmatic form of The Chief. The case that binds them harks back to the April of 1943, when four young boys illicitly foraging in the grounds of Hagley Hall in Worcestershire made a grisly discovery inside a tree. Itself resembling a thing of nightmare, ‘the Wych Elm’, as it was locally known, was acting as coffin for the body of a woman, apparently ritually murdered and hidden there two years previously. Though no one came forward to identify her, graffiti started appearing across the region, asking: WHO PUT BELLA IN THE WYCH ELM? Is she the woman that my fictional detective, Ross Spooner, has been seeking since, on hearing the confession of a German spy captured in the Fens, The Chief sent him to the Midlands to find the elusive Agent Belladonna?

It is certainly the most intriguing mystery I have ever had the fortune to pursue. The many links between spies, Spiritualists, stage magicians and witchcraft covens, coupled with a breathtaking real life backdrop, might at first seem a little far-fetched. But I can promise you that all the weirdest details and strangest characters in this book are those I haven’t made up. And that’s… magic.

Get your copy of That Old Black Magic with 10% off & free UK p&p

Join the seance on social: #ThatOldBlackMagic