02 June 2023

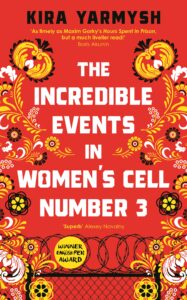

Winner of a PEN Translates Award

‘The whole world through a single cell: frightening and funny, absurd and all too real’ Julia Phillips, author of Disappearing Earth

‘As unpredictable as it is damning’ Wall Street Journal

‘Kira Yarmysh has succeeded in creating a sensitive, angry, and often funny portrait of Russian society’ Deutsche Welle

When Anya is arrested at a Moscow anti-corruption rally under false pretences, she is given a 10-day sentence at a detention centre. Her cellmates are five other ordinary women arrested on petty charges.

Ten listless days stretch before Anya and, as she appeals her sentence and recalls her progress from apolitical youth to informed citizen, she is troubled by strange, dreamlike visions, and wonders if her cellmates might somehow not be as ordinary as they seem.

A brilliant exploration of what it means to be marginalized both as an independent woman and in an increasingly intolerant Russia in particular, The Incredible Events in Women’s Cell Number Three introduces one of the most urgent and gripping new voices in international literature.

Read an extract below.

Order your copy: Waterstones | Bookshop.org

DAY ONE

If you asked Anya which day in prison had been the most trying, she would say the first. It had seemed both insane and endless. Prison time was elastic: it stretched out interminably, only to then fly like an arrow.

It started with her waking up on a clammy, impermeable mattress in a detention cell in a Moscow police department. She had been arrested the day before, but her efforts to outrun the riot police, her journey in the police bus, and her registration at the police department had kept her busy enough to all but overlook how it had ended. The reality of being in police custody struck her only once she was locked in that cell.

She had spent the night tossing and turning on the mattress, trying to pull her top down to avoid her body coming into contact with the oilcloth. The mattress was on the floor, there were no pillows, no blankets, and it was impossible to get comfortable. Either the arm under her head went numb or she got pins and needles in her side. She could only tell that she had managed to get some fitful sleep when she jerked awake, which happened many times.

What the time was, she had no idea. The cell was windowless, with only a dim light bulb above the door, which stayed on night and day. Her phone had been taken from her. Each time she woke, for want of anything else to do, she entertained herself by inspecting the wall in front of her: the peeling paint that looked like crushed eggshells; the suspicious streaks whose origins she preferred not to think about; the graffiti: Lex, Up Biryulyovo!, Allahu Akbar. Waking up one last time with a jolt, Anya realized she was not imagining it: she could feel a tremor under the floor, the metro must be open, morning had arrived.

The police department began coming to life, as Anya could hear through her cell door, which had been left ajar overnight. A kindly, older cop had not locked it but left it open a handbreadth. (A chain on the outside ensured she opened it no farther.) She lay, listening to the police arguing among themselves in the reception area, the telephone ringing off the hook, the rasping of a door lock, water flushing in a toilet she was eventually taken to visit. A policeman let her in and stayed outside to keep the door shut.

Anya dithered and looked around her. A scene from Trainspotting came to mind, where the main character goes to “the worst toilet in Scotland.” He had clearly seen nothing like the one in the Tverskaya

police department, with its chipped tile floor awash with murky fluid. A rusty chain hung from the water tank, and as for the toilet itself, it was a hole in the ground. Anya decided against going anywhere near

it. Running the faucet for appearances’ sake, while avoiding all contact with the squishy remnant of soap on the filthy edge of the washbasin, she emerged, and the policeman took her back to the cell.

Time passed with demoralizing slowness. Her cell door was now shut tight and did not allow in any outside sounds. She ran her eyes over the walls, which were barely visible in the dim light, but it was

an unrewarding pastime. She felt heavy and clumsy from lack of sleep, and thoughts stirred sluggishly in her head. Anya could not tell how long she sat like that. Her heart seemed to begin beating more slowly

and she felt she was sinking into a trancelike state; perhaps, indeed, suspended animation. When the door opened and a policeman came into the cell, Anya was startled, not sure what was happening.

She was taken through to the reception desk and told to sit on a bench next to a sad-eyed woman who looked Roma, a young guy who was drunk, and a man with a large black eye. The fatherly cop who

had left her door partly open took the box of her belongings out of a closet. “Get yourself together,” he said. “You have to go to the court hearing.” Anya turned on her phone, quickly checked her messages,

put her belt back on and laced up her sneakers. (The laces had been taken from her before she had spent the night in the cell.)

“Don’t make too much effort,” the cop advised. “You’re going to court.”